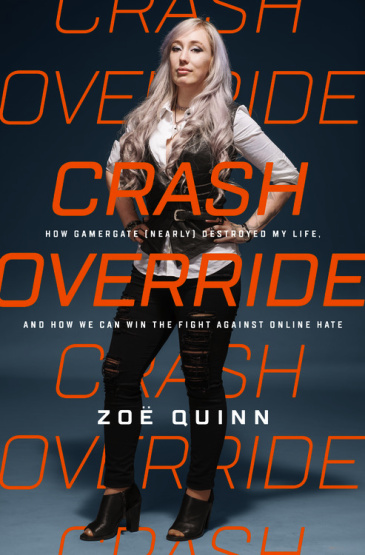

"I find myself having to frequently explain completely incomprehensible nonsense," game maker Zoe Quinn writes in her new book Crash Override. "And it's hard to bond with someone when they can't understand you."

This sentence sums up Quinn's memoir-length attempt to grapple with her Internet experience, which has become too common: as Gamergate's "patient zero" as she puts it, she was a highly visible target in an Internet harassment, abuse, and threat campaign. To give us a sense of what that was like, she writes about her early life growing up poor, offers a primer on the hate-filled corners of the Internet, guides us through how the judicial and police systems view the online world, and tries to deliver a comprehensive look at the ways marginalized people face abuse on online platforms. That's a pretty tall order for 238 pages.

Quinn hasn't necessarily written a guide to online hate that can be handed to Internet-culture outsiders, and she sometimes struggles to connect larger social issues to her complicated personal history. But she doesn't fumble this effort, either. Crash Override combines a brisk pace, candid stories, and embedded insight. Quinn's first book has its uneven moments, but it's important stuff for anybody interested in how online discourse has shifted over the past two decades.

Defining the G-word

The book comes with a long subtitle: "How Gamergate (nearly) destroyed my life, and how we can win the fight against online hate." Though there are many definitions of Gamergate at this point, Quinn views it as one arm of a larger social and political movement.

"Gamergate wasn't really about video games at all so much as it was a flash point for radicalized online hatred that had a long list of targets before, and after, my name was added to it," she writes. "The movement helped solidify the growing connections between online white supremacist movements, misogynist nerds, conspiracy theorists, and dispassionate hoaxers who derive a sense of power from disseminating disinformation." She goes on to argue that the people who identified with this movement "became a real force behind giving Donald Trump the keys to the White House."Crash Override's biggest success is in connecting the dots to clarify Gamergate's mission. In some ways, Quinn is simply taking ownership of a word that changed her life forever. But more importantly, she's unmasking the often-hidden methods used by many online hate groups. She has done her research and uses ample references to forum posts, IRC channel logs, and other documented Internet posts to identify the tactics used by anonymous Internet posters to both directly intimidate Quinn and publicly obfuscate any appearance of a unified attack.

One such plan revolved around an e-mail campaign aimed at anybody who might employ either Quinn or her known friends and allies—all while simultaneously raising money for an apparent "anti-harassment" charity. "The object is to cause infighting and doubt within SJW [social justice warrior] ranks," an anonymous person wrote in an intercepted chat log that Quinn republishes in the book.

Quinn describes the movement's earliest moments: anonymous e-mails were sent to anybody she was affiliated with, full of nude photos from Quinn's pseudonymous modeling days. The people e-mailing threatened that if her friends didn't distance themselves from Quinn, they'd be targeted next. She describes a phone call with her father in which he confirmed receiving a litany of strange prank calls revolving around "Five Guys Burgers and Lies"—a reference to a sexually charged slogan employed by Quinn's scorned ex-boyfriend Eron Gjoni in a notorious 2014 manifesto. (Quinn points to this phrase's malicious intent and says that the manifesto "weaved in-jokes and memes the way corporate brands do when they're trying to court a young, tech-savvy demographic.")This recounting of anonymous vitriol, along with the retelling of Quinn's early life on the Internet, mostly succeeds in clarifying jargon for anyone new to terms like "SWATing," "dogpiling," and "brigading." The book still makes readers swim through a thick soup of nerd-anese, however, and that may prove difficult for anyone unfamiliar with sites like Something Awful and 4chan, let alone those who are clueless about Reddit.

While some of Quinn's stories won't be new to anyone who has kept up with Gamergate and its fallout, Quinn clinches the book's importance by offering a compelling explanation of how online agitators attract so many followers.

First, there's her lengthy takedown of a group she calls "Internet Inquisitors." These are writers and YouTube channel hosts who "validate feelings and provide guidance" in order to "confirm a mob's hatred, paranoia, and insecurities and direct it toward the nearest combustible witch on their radar." (She opts not to name any of them, but it's easy to guess who she's referring to in certain examples, particularly former Breitbart columnist Milo Yiannopoulos.) Quinn became intimately acquainted with this trend of Internet provocateur after seeing her face and stories front and center on certain YouTube channels. Then she saw some of those video creators appear in Gamergate-affiliated IRC channels to "workshop" their next Quinn-related videos to their target, angry audience.

Quinn discovered her face plastered on Internet-outrage videos with titles like "Raped by Zoe Quinn: Why We Need Meninism."

Quinn counted how much time one YouTube channel dedicated to savaging game-culture critic Anita Sarkeesian over a period of nearly three years. The total: more than 3,500 minutes, or 58 hours.

As critical as Quinn is of these creators, she's more disturbed by a "poisonous" trend on content sites. Platforms like YouTube and Facebook allow hate to spread by combining content-neutral algorithms (which turn a blind eye to whether content violates a site's terms of service) with an economy of attention (which grants value to anything that garners quick clicks). These algorithms are easily gamed, she says, and the result is social media that favors tons of views, no questions asked, over asking pointed questions about what exactly drives those clicks.

Crash Override takes that seemingly obvious social-network issue and humanizes it in striking fashion. She tells us how it felt to find her face plastered on Internet-outrage videos—auto-suggested to her, of course—with titles like "Raped by Zoe Quinn: Why We Need Meninism." For months, her top auto-complete result on Google was "Zoe Quinn Five Guys." Her friends complain that Quinn's private Facebook posts are being matched with "suggested posts" accusing her of trying to infect people with HIV. "Content-neutral algorithms can turn the Internet into a popularity contest in which the people who want to see you fail are the only ones motivated to vote," she writes.

reader comments

331