The 2016 US election and subsequent fallout seem certain to occupy a unique place in the history books. Donald Trump’s campaign against Hillary Clinton was marked by incredible events and statements, from racism to misogyny. But perhaps the most startling and remarkable revelation is that a growing body of evidence indicates that Russia tampered with the election, and questions are being raised about President Trump’s ties with Russia.

Aside from the suggestion of targeted hacks in favour of Trump, it has been claimed that the fingerprints of Russian intelligence were all over much of the partisan disinformation about Clinton. And while it may seem outlandish and even risible to suggest Russia would go to such lengths to undermine opponents, the reality is that Russia has long mastered this art of dezinformatsiya. To see this, we need only look at the awful history of a science myth that refuses to yield, and still costs lives: the claim that HIV and Aids are man-made diseases.

To understand the origin and consequences of this tragic falsehood, we need to first understand the rationale of disinformation in warfare, whether overt or covert. Unlike misinformation, disinformation is constructed to be deliberately false, with the intention of sowing discord in enemy ranks. While there are undoubtedly historical examples, the industrialisation of disinformation emerged with the modernisation of media and mass communication. This is reflected in the etymology of the word itself, which by the advent of second world war had arisen independently in both Russian and English to characterise the spread of propaganda across Europe. Russia quickly recognised its enormous potential, and as early as 1923 the GPU (forerunner to the KGB) had established an office dedicated to it.

Disinformation fast became an integral part of Soviet intelligence, and by the birth of the KGB in the 1950s, it had become an essential component in the doctrine of “active measures”, the art of political warfare. Active measures included media manipulation, the use of front groups, counterfeiting of documents, and even assassinations when required. It was the very heart of Soviet intelligence, described by KGB Major General Oleg Kalugin as:

... not intelligence collection, but subversion: active measures to weaken the west, to drive wedges in the western community alliances of all sorts, particularly Nato, to sow discord among allies, to weaken the United States in the eyes of the people of Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America, and thus to prepare ground in case the war really occurs.”

Throughout the cold war, the Soviets were virtuosos in creating tensions between allies. In particular, they excelled at the use of “black propaganda”: crafting damaging material which purported to be from the other side. These attempts were nebulous and prolonged, and included Operation Neptune, a 1964 attempt to use forged documents with the intention of implying western politicians had supported the Nazis. While this was quickly exposed as a counterfeit, other ruses were more successful. Whilst dezinformatsiya was targeted chiefly at theUS, it was largely ignored there until 1980, when a Soviet forgery of a presidential document claimed that the administration was supportive of apartheid. This got some traction in US media, and so appalled president Jimmy Carter that he demanded a CIA inquiry.

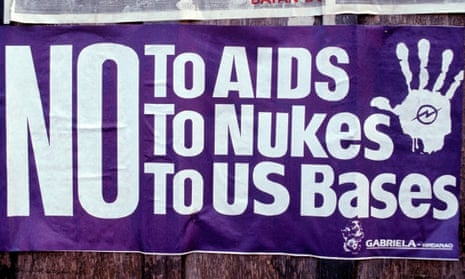

The resulting report found evidence of Russian-planted falsehoods throughout the world, including counterfeit documents that suggested America would use nuclear weapons on her own allies. The election of Ronald Reagan as president was anathema to the Soviets, and as it became clear he was seeking a second term, KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov decreed that it was imperative all KGB foreign intelligence officers, regardless of office, took part in active measures. In 1983, the KGB instructed its American operatives to move against Reagan’s possible re-election, and stations the world over were ordered to popularise the slogan “Reagan Means War”. Despite the efforts of Soviet intelligence, this failed miserably and he was re-elected in a landslide.

However, the Soviets had learned something powerful: whilst outright interference was difficult, undermining trust in an adversary was much more fruitful. The KGB wasted no time in crafting elaborate conspiracy narratives, planting claims that both John F Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr had been assassinated by the CIA. They also found a receptive audience for stories that water fluoridation was a government plot for mind and population control. This still has a devout core of believers, despite being long since debunked. But while such positions might be wrong-headed yet largely harmless, what was to transpire in the early 1980s was anything but.

In June 1981, a cluster of five unusual cases in Los Angles had captured the attention of the Centre for Disease Control (CDC), where young and otherwise healthy young men were presenting with symptoms usually only encountered in those with extremely compromised immune systems. More cases rapidly emerged around the US, primarily affecting homosexual men.

Confounded by the new disease, in 1982 researchers dubbed it GRID – Gay-related immune deficiency. But within months, cases were seen in intravenous drugs users, haemophiliacs and Haitian immigrants. By 1983, the illness had acquired its modern name: Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (Aids). By January of that year, researchers at the Pasteur Institute had isolated a T-cell killing retrovirus from an Aids patient, and Robert Gallo further showed this virus, named HIV, could lead to Aids. The CDC was quick to realise the dangerous extent of this pandemic, and pleaded with the White House for funds. Reagan was apathetic at best, largely ignoring pleas for funding.

The KGB saw an opportunity to foster discontent, in a project given the moniker Operation Infektion. The groundwork was laid as early as 1983 in an Indian pro-Soviet paper, which carried an anonymous letter from a “well known American scientist” where it was claimed Aids had been developed in a secret biological weapons laboratory in Fort Detrick. In 1985, retired biophysicist Dr Jakob Segal claimed that the Aids virus was synthesised by combining parts of other retroviruses: VISNA and HTLV-1. Soviet fronts the world over began reporting on “the Segal report”:

It is very easy using genetic technologies to unite two parts of completely independent viruses … but who would be interested in doing this? The military, of course … In 1977 a special top security lab … was set up … at the Pentagon’s central biological laboratory. One year after that … the first cases of Aids occurred in the US, in New York City. How it occurred precisely at this moment and how the virus managed to get out of the secret, hush-hush laboratory is quite easy to understand. Everyone knows that prisoners are used for military experiments in the U.S. They are promised their freedom if they come out of the experiment alive.

Despite being east German, Segal was presented as a French researcher to hide any communist affiliation. The report had the desired effect – by 1987 it had received coverage in over 80 countries and 30 languages, primarily in leftist publications. The dissemination followed a well-established pattern: the story would appear in a publication from outside the USSR, and was then presented as in Soviet media as the investigative work of others. To explain how Aids had become so prevalent in Africa, Radio Moscow claimed that a vaccination project in Zaire was in fact a deliberate attempt to infect Africans. Initially, at least, Operation Infektion had been a success – not only had it focused outcry towards the US, it had shifted attention away from Russian chemical and biological weapon development.

Of course, the problem with narratives is that reality doesn’t much care for them – Aids was very real, and Russia was not immune to it. The disease struck there in the mid-1980s, prompting Soviet researchers to seek the assistance of their American colleagues. This request was denied, with the Americans stipulating that no help would be forthcoming until the disinformation ceased. Whilst the Gorbachev administration attempted to derail American attempts to expose the disinformation, they eventually grasped the scope of the problem, and in 1987 Operation Infektion was officially disowned. It wasn’t until 1992 that the director of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), Yevgeny Primakov, conceded that the KGB had instigated and perpetuated the myth.But the damage was already done – once a rumour takes root, it is nigh on impossible to eradicate it entirely, and the myths planted by Operation Infektion were no exception. In the US, those predominantly affectedwere homosexuals and black people, groups long discriminated against. It is understandable that the idea Aids was a form of genocide might resonate with them, especially given the reticence of the White House to tackle the disease. A 2005 study published in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes showed that 50% of African Americans surveyed believed that Aids is a man-made virus; 15% also thought that it was a form of genocide against black people.

Once established, rumours mutate and grow far beyond their initial constraints – distrust of the “official narrative” also fed into Aids denialism, which claims that HIV does not cause Aids, and is instead a by-product of other factors, including the very anti-retroviral used to treat HIV. Publications like Continuum bought into this conspiracist narrative, and only ceased publication once all staff members had succumbed to Aids-related infections. Aids denialism in South Africa reached its zenith during the presidency of Thabo Mbeki, who denied a causal link between HIV and Aids. By the time he left office in 2008, he had created a harrowing legacy of more than 330,000 preventable deaths.

Operation Infektion is a timely reminder that falsehoods have serious consequence. The evolving Trump-Russia scandal is a potent reminder that the Soviet doctrine of dezinformatsiya has found a new lease of life under Vladimir Putin, who has used state media arms such as Russia Today and ‘troll factories’ to influence public opinion. These divide-and-conquer propaganda pitches extend far beyond the US, and appear to include attempts to influence the recent French election, stoke anti-immigrant sentiment in Germany and Sweden and may also have had an impact on the Brexit vote.

But whilst Russia may be the pioneer of this approach, the reality is that we all bear some responsibility. Today, spreading misinformation is orders of magnitude easier than it was in the 1980s, and in an era when 60% of us get our news primarily through social media, spreading propaganda requires only some webspace and an audience who are only too keen to like and share.

If we are to avoid the deleterious consequences of ‘fake news’, we need to sharpen our sense of scepticism and ask pertinent questions about the veracity of what we view and share. If we persist in disseminating falsehoods, we grant odious forces free rein to manipulate us, to our collective detriment.