by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: RyuFilms/Flickr/CC

REPORTS BY the Liberty Times, quoting an anonymous source, stated earlier this month that the Chinese government was seeking to train Taiwanese young people as influencers in order to popularize pro-China views.

According to the report, over 1,000 Taiwanese living in China have participated in training programs in Hangzhou, Xiamen, and Wenzhou, with the Chinese government carrying out these training programs as part of its “United Front” efforts targeting Taiwan. This includes a three-year show host training program run by the Hangzhou Taiwan Compatriots-Invested Enterprises Association, a program in Wenzhou’s Taiwanese entrepreneurship and employment center, and a program to offer training to 1,200 Taiwanese and over thirty online platforms by the Zhejiang provincial government.

Jaw Shaw-kong (right). Photo credit: 趙少康時間/Facebook

Jaw Shaw-kong (right). Photo credit: 趙少康時間/Facebook

After the report, Jaw Shaw-kong of the KMT also vowed that he would assist in efforts to train influencers in Taiwan. Jaw, a media personality currently contending for KMT chair, stated that he would seek to train pan-Blue Taiwanese influencers in a manner similar to the Chinese programs that were reported on by the Liberty Times.

With identity trends in past years illustrating rising Taiwanese identity and declining Chinese identity, particularly among young people, the training and recruitment of influencers proves a logical move by the Chinese government. Apart from the fact that young people consume a great deal of online content, such as created by influencers, in past years, surveys have shown that online influencer is currently one of the most desired professions in Taiwan. Many young people may be highly interested in training programs for influencers, with influencers viewed as a lucrative but also fulfilling and leisurely profession among youth.

In targeting influencers, the Chinese government has its sights on creating a new generation of spokespersons in Taiwan for pro-China views. Traditional spokespersons for pro-China views in Taiwan—such as politicians of the pan-Blue camp—no longer seem to be able to appeal to young people. Last November, the KMT had less than 9,000 party members under 40. With efforts by the KMT to change its aging image under current chair Johnny Chiang having run aground, it is a question whether the party will ever be able to change its youth-averse image. In order to avoid placing all of its eggs in one basket, then, it makes sense for the Chinese government to also cultivate spokespersons for pro-China views in the cultural sphere.

This would be both a carrot-and-stick approach. The Chinese government has clamped down on Taiwanese entertainers operating in the Chinese market that it views as supportive of Taiwanese independence, with actors such as Leon Dai or Lawrence Ko pushed out of the Chinese film industry for perceived pro-independence views or because of the pro-independence views of their family members.

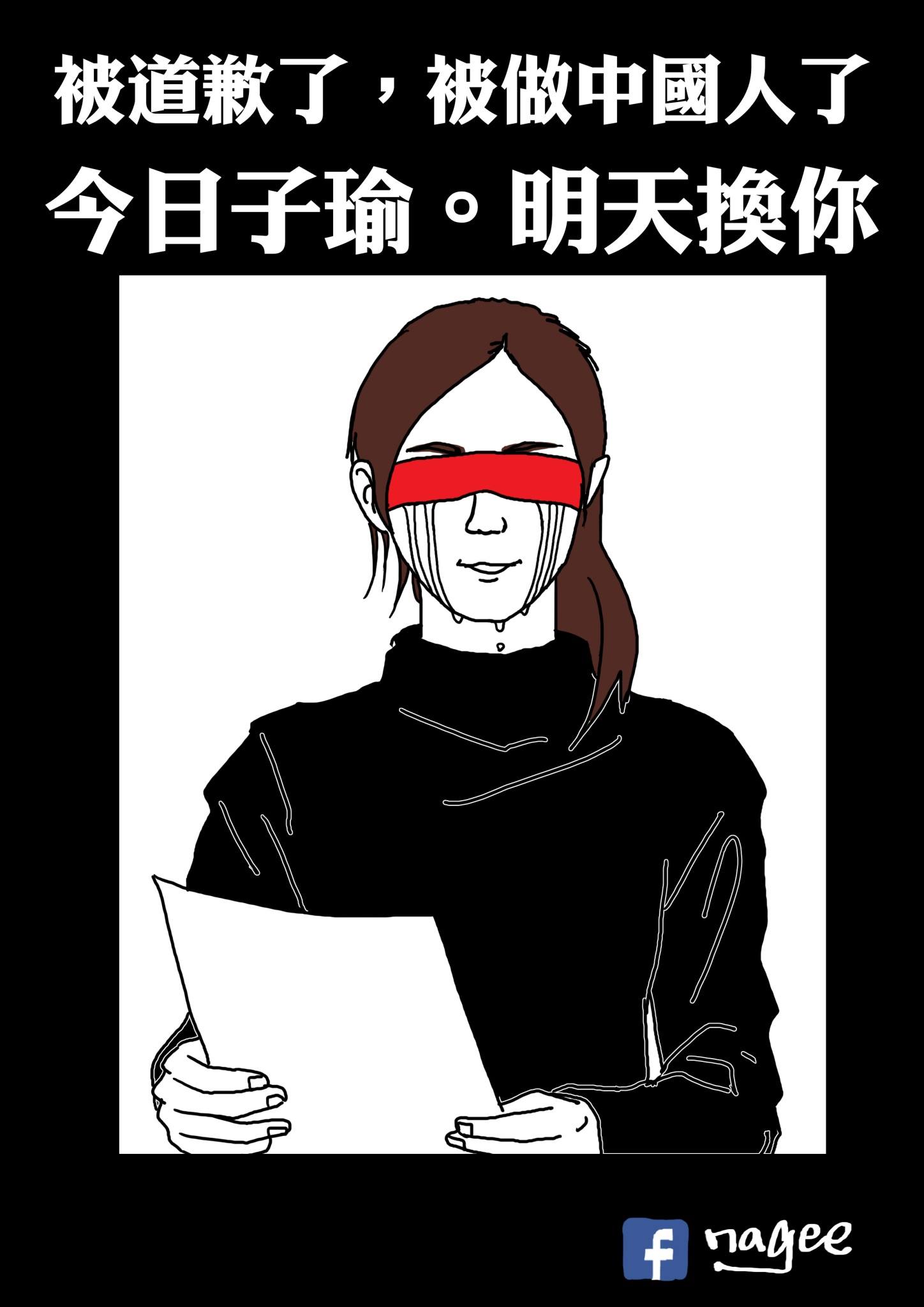

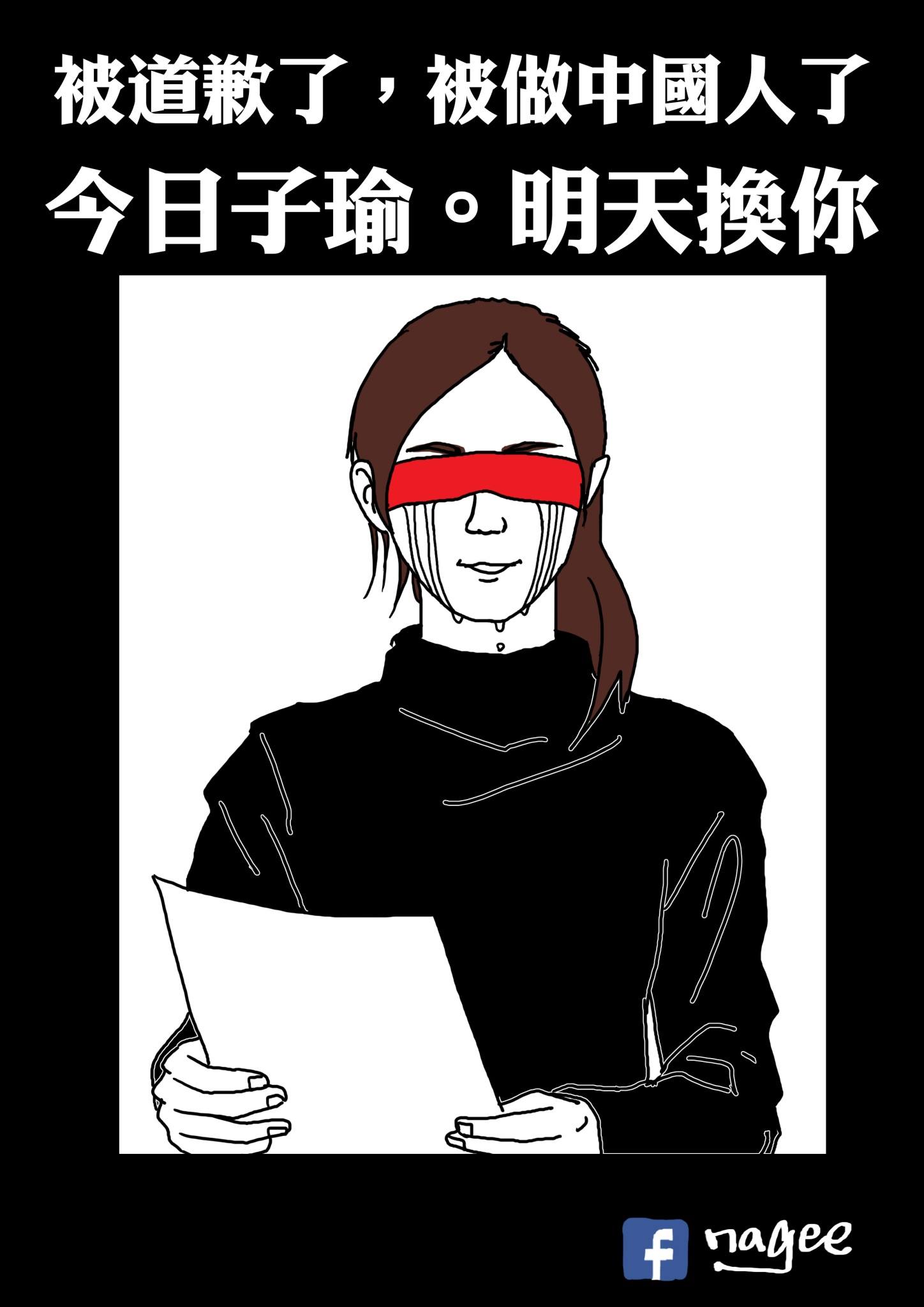

Webcomic about the Chou Tzu-yu apology incident. Photo credit: Nagee

Webcomic about the Chou Tzu-yu apology incident. Photo credit: Nagee

There have also been a number of incidents in recent years in which Taiwanese entertainers have apologized and publicly stated that they viewed themselves in Chinese after coming under scrutiny, including Chou Tzu-yu of South Korean K-pop group Twice, actress Vivian Sung, and others. Sometimes this takes place after backlash from nationalistic Chinese fans, prompting management companies to order the entertainers that they work with to publicly apologize.

More broadly, one can view Taiwanese entertainers working in China as a form of taishang, taishang being a term used to refer to Taiwanese business people working in China. With taishang traditionally viewed as staunchly pro-unification, in past years, the Chinese government has sought to cultivate a new generation of taishang. This has centered around the tech sector, with the Chinese government offering economic incentives, subsidies, and investment opportunities to young Taiwanese entrepreneurs that are willing to work in China.

But more broadly, with pro-unification views increasingly marginal among Taiwanese young people, the challenge facing the Chinese government is how to make pro-unification views “cool” among young people. With Chinese variety shows and streaming programs having proven popular in Taiwan, the Chinese government has sought to leverage on this as part of efforts to bring Taiwan back into the fold.

Two examples of job ads recruiting pro-unification streamers. Photo credit: 林雨蒼/Facebook

So, then, can one understand the participation of Chinese variety programs such as the Sing! China in the city-based exchanges conducted between Taipei and Shanghai under the auspices of Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je. Such programs invariably depict Taiwan as part of China and situate Taiwan within the greater China framework of including contestants from provinces across China—this has led to controversy in the past. Student protests against the depiction of Taiwan as part of China during a Voice of China event conducted on the National Taiwan University campus led to the 2017 NTU Sing! China incident, during which pro-independence student demonstrators were assaulted by pro-China gangsters.

Some controversies have broken out in past years regarding entertainers or media outlets that take pay from pro-China interests. This ranges from the controversy that resulted after late-night show host Brian Tseng accepted pay in return for allowing KMT presidential candidate Han Kuo-yu’s to appear on his talk show to the controversy after the Financial Times, Apple Daily, and other outlets reported that pan-Blue media outlets such as the China Times were directly accepting money and editorial directives from the Chinese government.

That being said, influencers may be the next front in the Chinese disinformation war. During the 2020 presidential elections, one observed suspicious social media campaigns thought to be of Chinese origin.

A hashtag campaign called, “#DeclaringMyVotingIntention,” for example, involved influencers declaring who they would be voting for online. However, this campaign was thought to be suspicious because of Taiwanese generally do not use the same vocabulary as Chinese.

Likewise, during elections in Taiwan, there have been reports of suspicious accounts offering to buy Facebook fan pages with large follower accounts, using vocabulary that suggested that these accounts were Chinese.

Examples of administrators of Facebook pages being approached by suspicious accounts hoping to buy their pages. Photo credit: 林雨蒼/Facebook

For Chinese disinformation to be more effective, it needs to avoid linguistic shibboleths that illustrate that disinformation is of Chinese origin. Recruiting Taiwanese to localize disinformation or otherwise disseminate pro-China views, then, is more effective than trying to have Chinese attempt to do the same while pretending to be Taiwanese. This, then, is what efforts to train young Taiwanese influencers are aimed at.

Webcomic about the Chou Tzu-yu apology incident. Photo credit: Nagee

Webcomic about the Chou Tzu-yu apology incident. Photo credit: Nagee