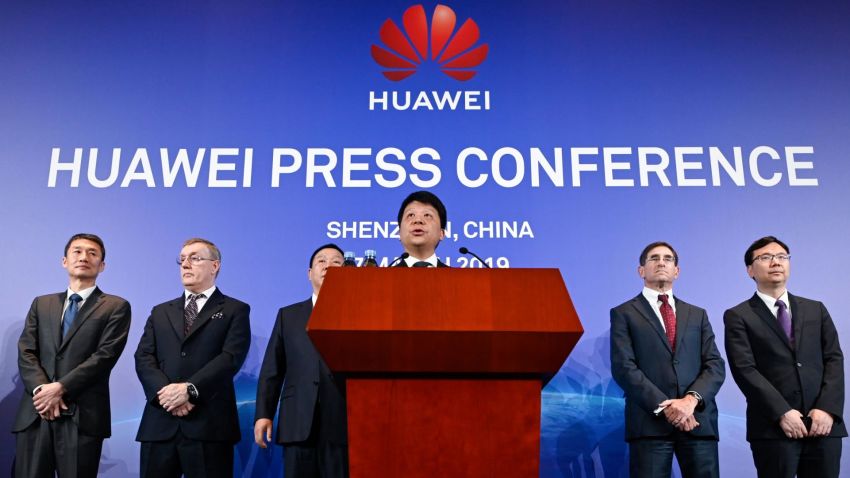

Huawei is one of the biggest and most controversial tech companies on the planet. Its products are at the heart of a clash between the United States and China that is straining longstanding alliances and may define the future of the internet.

The company started out small, selling cheap telephone switches in the 1980s in rural China. The story of how it grew into a business with annual revenue of more than $100 billion is one of naked ambition, government support and questionable business tactics.

Huawei is now battling a US campaign that aims to shut the Chinese company’s equipment out of the next generation of wireless networks, known as 5G. Ultra-fast 5G networks will be used to connect everything from mobile phones to self-driving cars.

Mobile operators like the UK’s Vodafone (VOD) and Canada’s Telus (TU) say banning Huawei could disrupt the rollout of 5G and undermine technological progress. But the US government claims Huawei gear could be used by Chinese intelligence services for spying on other countries. Huawei’s founder said the company has not been asked to share “improper information” and that it works independently of the government; the Chinese government denies stealing intellectual property and committing unfair trade practices.

If history is anything to go by, Huawei will fight tooth and nail to protect its business around the world.

Hungry like the wolf

Ren Zhengfei, a former engineer in the Chinese army, founded Huawei in 1987 and has been its CEO since 1988. His military background strongly influenced the company’s management style, resulting in what became known as Huawei’s “wolf culture.”

Ren wants his employees to stay hungry. He told CNN in an interview this month that the US campaign against Huawei will be good for employees that have become “lazy, corrupt and weak” after decades of success.

The CEO often talks about “wolf spirit” and has in the past told colleagues “to be shameless” in their efforts to secure business, according to “The Huawei Story,” a book about the company co-authored by Tian Tao. Tao is a member of the Huawei International Advisory Council, an organization affiliated with the company, and works at Zhejiang University in eastern China.

Huawei employees are expected to emulate wolves’ bloodthirsty nature, fearlessness, resilience to harsh conditions and ability to work as a team.

Huawei started out selling other companies’ products, but eventually decided to develop its own technology, throwing a lot of money and people into the effort.

According to “The Huawei Story,” the company outfitted a large industrial building with work spaces and a kitchen. Beds were set up against the walls and mattresses placed on the floors. Employees worked grueling hours, sleeping and eating on site.

The relentless work paid off. Within a year, Huawei had built its own telephone switching system.

Huawei’s early products were cheap and often broke down. But the company made a name for itself with its attentive customer service, getting equipment up and running again quickly.

In the decades that followed, Huawei continued to improve its products and introduce new ones, such as smartphones. And it began expanding internationally, sending executives to developing markets in Africa, South America and Asia.

Employees were offered generous financial incentives — those who hit or exceeded targets were well compensated for their efforts, according to several people who previously worked for the company.

A former project director who was based in several emerging markets in the late 2000s and mid 2010s, told CNN Business that his bonuses and annual dividends from company shares far outstripped his base salary. It was an effective way to recruit top talent because China’s other tech companies didn’t have such rich incentives, he said. Huawei recruited him from another Chinese telecommunications company, trained him briefly in Shenzhen, then sent him abroad.

“Money motivation is the only thing that works,” he said. “We are called ‘wolf culture.’ That means we’re wolves, we need meat, we need money.” He asked to remain anonymous because of fears that speaking out against Huawei could damage his career.

Employees were expected to keep cell phones on 24 hours a day. If customers called with problems at midnight, engineers were immediately deployed, according to the former project director.

He said the relentless schedule could burn people out. After nearly a decade with the company, he left because he was exhausted and rarely saw his family.

Huawei said employees have been known to work long hours, because if they grow the business they are rewarded enormously.

Backing from Beijing

The name Huawei roughly translates to “China is able.”

In the late 1970s, China’s telecommunications infrastructure wasn’t able to do much. The country lagged far behind other nations. Less than 0.5% of households had a telephone, according to the World Bank.

The poor infrastructure was a barrier to development. In the 1980s, Beijing opened the market to foreign companies like Japan’s Fujitsu (FJTSF), Sweden’s Ericsson, France’s Alcatel, America’s Motorola (MSI) and Finland’s Nokia (NOK).

It also nurtured domestic players. Two eventually emerged as leaders in China and around the world: ZTE (ZTCOF) and Huawei.

ZTE is state-controlled and publicly traded, while Huawei is a private company owned by its employees. But critics say Huawei has unfairly benefited from generous government support, according to Philippe Le Corre, senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School and co-author of “China’s Offensive in Europe.”

“There’s only one reason Huawei is so powerful, it’s because they received loans without interest from [Chinese state banks]. And that helped them to penetrate European markets,” he said.

Asked about Le Corre’s claims, Huawei spokesman Glenn Schloss said the company “has been transparent about financing.”

“There has been some misunderstanding about financing from state-related financial institutions, leading to an inflation of the role played in Huawei’s growth,” he said.

“This financing is usually provided to governments or operators of networks which undertake procurement or other activities to secure suppliers including Huawei,” he added.

Indeed, other global companies benefit from state investment or export-import banks that provide financing at favorable rates. But experts say China is just a lot more generous.

“While export credit programs are available in many countries, the United States, Sweden, and Japan included, the sheer size of the Chinese loans dwarf comparable programs in other countries,” according to a Center for Strategic and International Studies case study.

Between 2005 and 2011, China Development Bank agreed to provide as much as $40 billion to potential Huawei customers, according to Schloss.

Huawei said 35 global projects tapped into the available lines of credit between 2005 and 2011, with about $3 billion actually being extended.

“Huawei’s sales globally during that period were more than $145 billion. So the proportion attributable to credit lines has not been significant,” Schloss said.

Osvaldo Coelho, a veteran of the telecommunications industry who previously worked for Huawei as a project director in Mauritius and South Africa, says Beijing’s support was key to the company’s success.

“When you have a big market, and you have the backing of a big government all-powerful like the Communist Party of China, of course you’re going to grow,” he said. “This isn’t a startup in some garage.”

In 2012, the European Commission was set to launch a trade case against Huawei and ZTE, alleging that the Chinese state was illegally subsidizing the companies. The case stalled because rivals at the time reportedly declined to cooperate, fearing retaliation from Beijing. China’s foreign ministry at the time said Huawei and ZTE conform with international trading regulations.

Breaking the rules to grow the business

Like other global tech companies before it, Huawei has taken an aggressive approach to winning international business, even if that sometimes meant breaking the rules.

In 2003, Cisco (CSCO) sued Huawei for copying software and violating patents. Huawei later admitted in US courts that some of its router software was inadvertently copied from Cisco (CSCO). The American rival dropped the suit after Huawei promised it would modify its products.

Huawei’s global track record is dogged by “allegations of bribery, corruption and the pursuit of foreign political interference,” according to a February 2018 report from RWR Advisory Group, a Washington-based consulting firm that tracks China and Russia’s global business transactions.

In 2012, an Algerian court found Huawei and ZTE executives guilty of bribery and sentenced them to 10 years in prison.

In 2014, Huawei launched its own anti-graft campaign, and more than 4,000 employees admitted to violating various company policies, ranging from small misdemeanors to bribery and corruption. The employees came forward after Huawei promised leniency, Ren said in 2015 at the World Economic Forum.

“Huawei is committed to strictly adhering to all laws and regulations and to the highest standard of business ethics. This commitment is integrated into our Code of Business Conduct which governs the policies and practices that our employees are required to follow. We have zero tolerance for breaches,” the company said in a statement.

The US Justice Department disputes that claim.

In January, the department brought two cases against Huawei. US prosecutors are accusing the company of stealing intellectual property from US carrier T-Mobile (TMUS) and violating US sanctions on Iran. Court documents in the IP theft case detail an alleged scheme to pay employees to steal trade secrets.

Huawei said at the time that it was “disappointed” by the US move to bring charges against it. “The company denies that it or its subsidiary or affiliate have committed any of the asserted violations of US law set forth in each of the indictments,” it said in a statement.

Accusations of stealing intellectual property and bribing government officials are hardly limited to Huawei.

Global rivals including Alcatel, Ericsson, Samsung and Siemens have faced bribery and corruption scandals.

But Coelho says Huawei’s willingness to do whatever it takes to secure business stands out.

“If you’re hungry, you can do quite a lot of things, you can go really dirty,” he said. “They do in extreme what [others] used to do in their hay days.”

Huawei has employees in “very fast growing markets going out to do business with the rest of the world. We have 180,000 employees, we have a strict compliance policy, but things happen,” said Schloss.

“And when they do, we discipline or fine employees, and work with local authorities,” he added.